“Epistemology examines the foundations of truth, belief, and knowledge, seeking to understand how we distinguish what is true from what is not.”

— the Author

In an era dominated by digital information, mandatory schooling and plethora of universities, omnipresence of libraries and bookstores, and thousands of news outlets, the question “How do we know what we know?” may initially seem absurd, philosophical, or abstract, yet it remains profoundly relevant. In today’s landscape, where misinformation is rampant, and where the majority of what we learned in school and take for granted is wrong and a lie and the majority of what is presented to us by media and movies is leftist or rightist propaganda, understanding the foundations of knowledge—epistemology— has never been more crucial.

The crisis of misinformation was starkly highlighted during the COVID-19 pandemic and the reasons for current war in Ukraine, raising serious doubts about the existence of unbiased, objective truth which – nobody seemed to be able to deliver.

Why is that and is there something like unbiased objective truth?

Truth is an Interpretation of Facts

The concept of truth has traditionally been seen as singular and absolute—a constant, unwavering beacon in the pursuit of knowledge. However, in our complex, interconnected world, the notion of a single, objective truth has become increasingly elusive. Truth appears fractured, shaped by context, perspective, and power. The more we examine how truth is presented, the clearer it becomes that it is not a monolith but a multifaceted, often conflicting set of realities.

Historically, philosophers have grappled with the nature of truth, debating whether it is universal or relative, eternal or temporal, discoverable or constructed. Plato envisioned truth as a perfect form, accessible only through nous (the divine part of the soul). In contrast, Nietzsche declared that “there are no facts, only interpretations,” emphasizing the subjective nature of human perception. Today, these philosophical debates are not just academic; they lie at the heart of our societal struggles with misinformation, propaganda, and polarized worldviews.

Difference between Truth and Facts

Facts are often perceived as objective, but they are always influenced by interpretation. Every memory is shaped by the bias of the person recalling it, and even scientific facts are limited by the precision of the instruments used in measurements. What we consider truth is often an approximation of facts, subject to the tools and perspectives that frame them. You may claim that a wall is white, but in reality, it’s a shade of gray—due to the materials it’s made of, which absorb and reflect light at different wavelengths. Photographers, in their attempt to capture the “truth,” adjust the white balance because “white” itself varies depending on lighting conditions. Imperfections at both the microscopic and atomic levels, material properties, lighting conditions, and surface irregularities mean that even the most “white” walls are slightly off-white. Pure white is unattainable, just as pure objectivity is.

If you ask someone to tell you “just the facts,” it’s an impossible task. What they offer is their truth, shaped by their own perception. Facts are elusive, constantly filtered through interpretation, making objectivity unattainable. Thus, truth and facts are inseparably intertwined, with no fact entirely free from bias or interpretation.

Truth – One or Many?

The modern landscape demonstrates that truth is often contingent upon the lens through which it is viewed. It is shaped by those who wield it and by the contexts in which it is applied. From scientific discoveries and political narratives to personal beliefs and spiritual convictions, truth reveals itself as a tapestry of perspectives—each claiming legitimacy, yet often at odds with one another. This raises critical questions: Can all these truths coexist? Are some truths more valid than others? And how do we navigate this complex terrain without losing our grasp on reality?

In this essay, I propose a framework that categorizes truth into four distinct yet coexisting domains: Scientific, Political, Human, and Divine. Each of these truths possesses intrinsic contradictions that are reflected in their nature, consequences, and virtue or morality. Scientific, Political, and Human truths can be understood through their nature—whether they are innovative and progressive or rigid and dogmatic; through their consequences—whether they are liberating and empowering or stifling and disempowering; and through their virtue or morality—whether they are good or bad. These dichotomies highlight the complex ways in which each type of truth influences our perception of the world and impacts society, often in conflicting and contradictory manners.

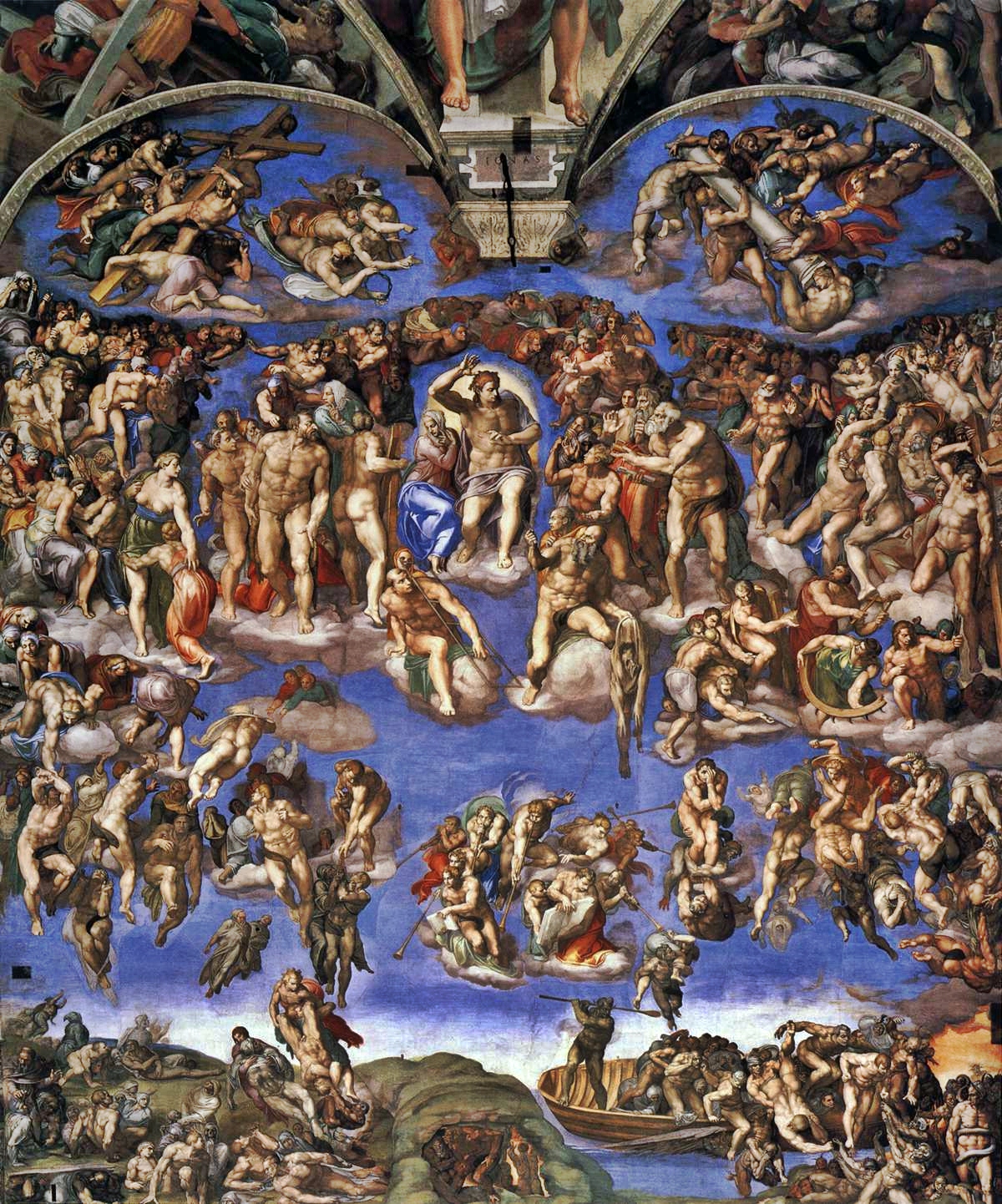

In contrast, Divine Truth stands apart as one and absolute. Although transcendent—and sometimes elusive and difficult to understand because of the limitations of human perception—it remains the ultimate truth we need to strive toward. Divine Truth does not fluctuate between dichotomies of nature, consequences, or virtue and morality; it exists beyond these human constructs, offering a sacred and unchanging standard that transcends the imperfect and often conflicting truths found in our worldly experiences.

Scientific or “Objective” Truth: The Evolving Knowledge

Science is often viewed as the beacon of truth and knowledge. Echoing Heraclitus’s philosophy that “πάντα ῥεῖ” (everything flows), we recognize that scientific truth is not static but in perpetual flux. At its core, science is less a collection of absolute truths and more a set of investigative methods and processes, most prominently induction and deduction. These methods drive the pursuit of knowledge through observation, experimentation, and reasoning, allowing us to understand and interact with the world. However, the truth revealed by these methods is always tentative, subject to revision or rejection as new evidence emerges.

Despite its foundational nature as an evolving and exploratory practice—which dates back to Plato and Aristotle and continued through scientists deeply connected to the Church, such as Gregor Mendel, Roger Bacon, Nicolaus Copernicus, and Georges Lemaître—science during the Enlightenment and afterward became increasingly dogmatic, particularly during the rise of logical positivism. However, this shift did not originate with the scientists themselves, who largely continued to view their work as a method of inquiry into the natural world. Instead, it was driven by philosophers who had little to do with science but were eager to dismantle Europe’s Christian legacy and replace it with their own dogmatic vision of empiricism.

Philosophers like Auguste Comte, David Hume, Immanuel Kant, and the Vienna Circle members (including Ludwig Wittgenstein, Moritz Schlick, and Rudolf Carnap) elevated science from a set of investigative methods to the status of an ultimate authority. They pushed the narrative that empirical evidence alone was the hallmark of truth, dismissing religious and metaphysical insights as meaningless relics of the past. These philosophers were not practitioners of science; they were ideologues whose primary agenda was to undermine traditional values, particularly those rooted in Christianity, and replace them with a cold, materialistic worldview.

Their version of science was stripped of its true exploratory nature and repackaged as a rigid doctrine that claimed to explain all aspects of existence. This blind faith in science led to a materialistic worldview where no truth was considered to exist beyond the scientific realm. Philosophers and ideologues, eager to reshape society in their image, propagated the idea that science alone could explain everything—effectively turning it into a dogma that stifled alternative perspectives and reduced the rich complexity of human existence to mere empirical data points.

This transformation of science into a quasi-religion was a betrayal of its roots. True scientists—figures like Isaac Newton, Johannes Kepler, Albert Einstein, and Gregor Mendel—often held deep spiritual beliefs and saw their work as complementary to their faith, a nuance ignored by the philosophers who elevated science to a dogma. Newton saw his work as uncovering the laws of God’s creation; Einstein believed in the harmony between science and the divine; Mendel, a monk, made his groundbreaking discoveries in genetics under the guidance of his religious beliefs. These scientists never claimed that science could or should replace the moral and metaphysical insights provided by religion.

While religion provides a moral compass and the hope of something greater beyond our understanding, science, when turned into dogma by these philosophically-driven agendas, strips away all its meaning and leaves us with—nothing. This shift, orchestrated by philosophers who were more interested in tearing down existing values than in the pursuit of genuine scientific discovery, has left a legacy of disillusionment and an impoverished view of the world.

Nature: Investigative vs. Dogmatic

Scientific Truth ideally embraces investigation, continually challenging existing ideas and exploring new frontiers. However, history shows that entrenched beliefs and authoritative figures have often stifled innovation. Thomas Kuhn’s concept of paradigm shifts illustrates how scientific communities can become resistant to change, clinging to established theories until groundbreaking discoveries force a radical shift in understanding. Kuhn argued that science progresses not through a steady accumulation of knowledge but through revolutionary changes that disrupt existing paradigms. This tension between openness and dogmatism demonstrates how science, despite its methods, can sometimes behave like the very dogmas it aims to transcend.

Consequence: Liberating vs. Stifling:

Science’s potential to liberate is evident when it empowers us to challenge ignorance, improve lives, and expand our understanding of the universe. Yet, it can also become stifling when wielded as an unquestionable authority that suppresses alternative viewpoints. During the Enlightenment and especially the rise of logical positivism, science was elevated to the status of ultimate authority, often dismissing religious and metaphysical insights as meaningless. The prioritization of empirical evidence while sidelining other forms of understanding was even criticized by atheists like Karl Popper. He criticized this dogmatic approach, particularly the strict adherence to verificationism promoted by logical positivists. Popper argued that this narrow focus on empirical verification excluded many valuable scientific theories that could not be conclusively verified but could be tested and potentially falsified. Popper’s emphasis on falsifiability as the criterion for scientific inquiry highlighted the importance of keeping science open to new, challenging ideas rather than confining it to rigid empirical boundaries.

Recent developments represent a liberating turn within scientific inquiry, challenging rigid materialism and opening new dialogues between science and spirituality. As noted in my article “The Trinity Through a Mystical Lens: Understanding the Divine Force, Principle, and Presence”, scientific findings such as the Borde-Vilenkin-Guth (B-V-G) Theorem and evidence from entropy suggest a cosmic beginning, hinting at an intelligent force behind the universe’s creation. These insights challenge the once-dominant belief in an eternally static universe, proposing instead that the universe had an inception point necessitating a cause beyond physical reality.

Furthermore, studies into near-death experiences and the philosophy of mind suggest a transphysical dimension of consciousness, inviting us to reconsider the boundaries of scientific and spiritual understanding. This liberating aspect of modern science offers a more inclusive approach, recognizing that the search for truth need not be confined to the material world alone.

Scientific Truth, therefore, is a dynamic process—a balance of investigation and resistance, liberation and constraint. Recognizing its limitations and potential allows us to engage with science not as a final arbiter of truth but as one path among many in the human quest for understanding.

Virtue: Moral vs. Immoral

Scientific Truth also grapples with moral and immoral applications. Science is inherently neutral—a tool that reflects the values of those who wield it. Morally, science has driven advances in medicine, environmental protection, and technologies that improve quality of life. However, it has also been used immorally, often bringing about degradation, suffering, and unforeseen consequences before eventually turning towards solutions.

Throughout history, scientific advancements have frequently introduced new problems before contributing to human progress. The Industrial Revolution, for instance, initially brought about unprecedented levels of pollution, inhuman labor conditions, and sparked social unrest, such as the Luddite revolts against mechanization. London was trapped in smog for over 200 years, and the Rhine River was so heavily polluted by the BASF chemical industry that it was famously said you could develop a film roll in its waters. Only after decades of suffering did technology advance to create cleaner production methods and improved working conditions, but not before leaving a legacy of environmental damage and social upheaval that even contributed to movements like the communist revolution.

Similarly, scientific innovations have often escalated the brutality of warfare, as seen in the development of more efficient weapons that have perfected the art of killing. The advancement of nuclear energy, which held the promise of a powerful new energy source, was initially driven by the desire to build the atomic bomb—a weapon that has since left humanity living under the shadow of potential nuclear annihilation. Science’s darker side is further exemplified by unethical experiments on human beings, from the notorious experiments conducted by Josef Mengele during World War II to contemporary human trials, which sometimes take place without proper consent or ethical oversight, especially in contexts like military research.

Even today, the rapid pace of scientific progress often appears more dystopian than utopian. While technology has connected the world through smartphones and computers, it has also disrupted human relationships, deepened social alienation, and raised concerns about privacy, mental health, and the loss of authentic human connections. The moral dimension of science hinges on the intentions and ethical considerations of its application. When science prioritizes profit, power, or political gain over the welfare of humanity, it crosses the line from being a force for good to becoming a tool of harm.

Recognizing the moral implications of scientific work is crucial to ensuring that science remains a servant of human progress rather than a master of exploitation. It serves as a reminder that while science seeks to uncover the truths of the natural world, it must always be guided by a sense of responsibility, ethical oversight, and a commitment to the well-being of all. Only through this awareness can science truly fulfill its potential to improve life rather than degrade it.

Political Truth: The Art of Demagogy

Political truth often emerges as a carefully crafted narrative designed to sway public opinion and win elections. Unlike scientific truth, which is grounded in empirical evidence, political truth is fluid, shaped by the motives and agendas of those in power. These truths are frequently tailored or distorted to appeal to specific demographics, fitting neatly into the agendas of political entities—like “Woke” culture, political correctness, Christian nationalism, and libertarianism. This manipulation of truth for political gain obscures genuine facts and fosters widespread cynicism and mistrust among the populace.

Nature: Adaptive vs. Rigid

Political truth can be adaptive, responding to new information, societal changes, or evolving public sentiments. When political truths are adaptive, they have the potential to reform systems, address injustices, and create policies that reflect the needs of the people. A prime example of adaptive political truth is Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal, which was crafted in response to the Great Depression. FDR’s policies represented a significant shift in government intervention in the economy, adapting to the urgent need to address widespread unemployment, poverty, and economic instability. By implementing new social safety nets, regulatory reforms, and public works programs, the New Deal reflected an adaptive approach that reshaped American society and helped pull the nation out of economic despair.

However, political truth often becomes rigid when it is locked into ideological narratives that resist change, even when confronted with new evidence or shifting realities. Rigid political truth is exemplified by the persistence in the continuation of unwinnable conflicts, such as the Vietnam War. Despite mounting evidence and internal reports, like the Pentagon Papers, indicating that the war was unwinnable and increasingly unpopular among the American public, political leaders continued to escalate the conflict. This rigidity, driven by a refusal to admit failure and the fear of losing political face, resulted in prolonged suffering, loss of life, and deep divisions within society. The inability to adapt to the changing realities of the war showcases how rigid political truths can have devastating consequences.

Consequences: Empowering vs. Exploitative

At its best, political truth can be empowering, fostering civic engagement, encouraging transparency, and aligning policies with the needs of citizens. This form of political truth seeks to enlighten the public, promote accountability, and support democratic values. An example of empowering political truth is Nelson Mandela’s fight against apartheid in South Africa. Mandela’s leadership and messaging united a deeply divided nation, emphasizing reconciliation, human rights, and the value of democratic principles. His approach fostered a sense of collective hope and engaged citizens in the process of rebuilding their country, turning a long-standing system of oppression into an opportunity for national transformation.

Yet, more commonly, political truth is exploitative—crafted to control, mislead, or divide. Leaders use exploitative political narratives to distract from failures, scapegoat opponents, or rally support by appealing to base instincts like fear or anger. A clear example of this is Joseph McCarthy’s Red Scare in the United States during the 1950s. McCarthy’s baseless accusations of widespread communist infiltration were used to stoke fear and paranoia, exploiting public perception to gain power and silence critics. His tactics created a climate of distrust, ruined countless lives, and eroded civil liberties, showcasing how exploitative political truth can turn public discourse into a tool for personal gain and control.

Morality: Just vs. Corrupt

Political truth exists on a moral spectrum, oscillating between justice and corruption. Just political truth upholds the principles of fairness, accountability, and the public good. It is seen in policies that strive to protect human rights, promote social equity, and ensure transparent governance. An example of just political truth is the Civil Rights Movement in the United States, particularly the leadership of figures like Martin Luther King Jr. and the enactment of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. These efforts were grounded in the pursuit of justice, aiming to dismantle systemic racism, protect the rights of African Americans, and promote equality under the law. The movement galvanized public support and legislative change, showing how just political truth can empower marginalized communities and push society toward greater fairness.

Conversely, corrupt political truth is driven by self-interest, deceit, and exploitation. It manifests in the manipulation of information, the spreading of falsehoods, and the use of power to serve narrow interests rather than the broader community. A stark example of corrupt political truth is the Watergate scandal during Richard Nixon’s presidency. The scandal involved a web of lies, illegal activities, and abuses of power to undermine political opponents and cover up wrongdoings. Nixon’s administration engaged in deceit and manipulation of public trust, ultimately leading to his resignation. This corruption eroded faith in government institutions and highlighted how political truth, when twisted for personal gain, can destabilize democracy.

Corrupt political truth is also evident in authoritarian regimes, such as the widespread corruption under Venezuela’s Hugo Chávez and Nicolás Maduro. Their administrations used propaganda, election manipulation, and suppression of dissent to maintain power while plunging the country into economic ruin. The corruption and mismanagement have led to severe human suffering, showcasing how the distortion of political truth can devastate a nation.

Human Truth: The Moral Compass

Human or moral truth is deeply rooted in the principles of fairness, empathy, and compassion, influenced by concepts such as συμπάθεια (sympathy and empathy), στοργή (selfless care), and ἀγάπη (charitable love). This type of truth prioritizes the reduction of suffering and the enhancement of well-being, reflecting society’s collective ethical stance. It often leads to simplifications like “if God exists, he wouldn’t allow this…” Human truth is the expression of our deepest values, shaped by personal experiences, cultural norms, and our inherent sense of right and wrong.

Nature: Intuitive vs. Emotional

Human truth can be intuitive—insightful or stifling—where people sense that something is not quite right, driven by an inner moral compass. This intuitive aspect is seen when society collectively recognizes injustices or when individuals take a stand against perceived wrongs, even when such actions are unpopular or go against established norms. For example, the #MeToo movement represents an intuitive human truth, where many individuals felt that long-standing societal norms around power and sexual misconduct needed to be challenged. The movement was driven by a deep, intuitive sense that these behaviors were wrong and needed to be addressed, leading to a widespread call for accountability.

On the other hand, human truth can also be heavily emotional, driven by deep-seated beliefs that may be sympathetic or cruel. Sympathetic emotional truth often manifests in outpourings of support and solidarity, such as global humanitarian efforts following natural disasters, where people rally to aid those in distress out of a sense of shared humanity. However, emotional human truth can also be cruel, as seen in mob mentality or acts of retribution, where emotions override rational judgment, leading to actions that harm others, such as lynchings or public shaming without due process.

Consequences: Liberating vs. Stifling

Human truth can be liberating when it inspires positive social change, promotes understanding, and alleviates suffering. A powerful example of liberating human truth is the abolitionist movement, which arose from the moral conviction that slavery was an inhumane and intolerable practice. This truth, driven by empathy and the recognition of the inherent dignity of all people, galvanized efforts to end slavery, liberating millions and reshaping the moral landscape of societies.

Conversely, human truth can be stifling when it is used to justify actions that suppress others or maintain the status quo, often clashing with broader societal progress. For example, the defense of segregation in the American South was often framed as a moral truth by its proponents, who argued that it was necessary for maintaining order and traditional values. This stifling version of human truth resisted civil rights efforts and prolonged the suffering of marginalized communities, showing how moral convictions can sometimes be twisted to justify harmful practices.

Virtue: Moral vs. Immoral

Human truth naturally oscillates between what is seen as moral and immoral, often reflecting the complexities of human judgment. Morally driven human truth seeks to act in ways that reduce harm and promote the common good. This is seen in global humanitarian efforts, such as Doctors Without Borders, which operates on the principle that all lives are valuable, and medical care should be provided impartially to those in need, regardless of political or social barriers.

However, human truth can also become immoral when self-interest, bias, or hatred drive actions that harm others. Examples of immoral human truth include ethnic cleansing and genocides, where a group’s perceived moral justification for their actions leads to unspeakable atrocities. In these cases, what one group sees as a moral imperative—often fueled by fear, prejudice, or a desire for power—results in immense suffering and loss of life, showing how human truth can be dangerously distorted.

Human truth, then, serves as both a guiding light and a cautionary tale. It is deeply personal yet collective, capable of inspiring great good or justifying great evil. Recognizing the dual nature of human truth helps us navigate the moral complexities of our world, striving to align our actions with empathy, compassion, and a broader sense of justice.

Divine Truth: The Cosmic Order

In contrast to human-centric views, divine truth offers a broader perspective that considers the overall welfare of humanity. Divine truth transcends individual desires, societal norms, and human judgments, reflecting a cosmic order that encompasses the entirety of existence. Such truths may incorporate elements of natural selection and evolution, sometimes necessitating suffering and challenges as part of growth and character building. Divine truth, therefore, does not always align with individual notions of fairness but rather with a cosmic order that fosters long-term resilience and development.

Nature: Universal vs. Transcendent

Divine Truth is universal, encompassing all of existence, and transcendent—beyond human comprehension and limitations. It is perceived in events and principles that reflect a broader, often unseen, order. A classic example of the universal nature of divine truth is the law of cause and effect, often seen in both natural laws and spiritual teachings. This principle operates across all aspects of life, showing how actions have consequences, often beyond immediate perception. Divine truth is not confined to time, place, or culture but operates universally, guiding the moral and physical realms in ways that can be difficult for humans to fully grasp.

Divine Truth is also transcendent, as it goes beyond human logic and often challenges our understanding. The concept of Divine Providence—the idea that a higher power governs the fate of individuals and nations—is one such example. While the outcomes of divine actions, such as the prosperity or destruction of a nation, may seem arbitrary or unjust from a human perspective, they are believed to be part of a greater, incomprehensible plan that ultimately serves a higher purpose. This transcendent aspect reflects the mystery of divine truth, which does not conform to human reasoning or expectations.

Consequences: Pleasant vs. Unpleasant

Divine Truth can manifest in ways that humans perceive as either pleasant or unpleasant, depending on their context and perspective. Pleasant manifestations of divine truth include the concepts of forgiveness, love, and blessed life, where individuals experience grace, redemption, and spiritual fulfillment. For many, these positive aspects of divine truth are seen in moments of profound peace, answered prayers, or the perceived presence of divine guidance that leads to personal growth and joy.

However, divine truth can also appear unpleasant, reflecting the challenging aspects of cosmic order. Events like the Great Flood (Diluvium) in religious texts or natural disasters are often interpreted as manifestations of divine truth that serve a greater purpose, such as cleansing, judgment, or a reset of moral order. These events challenge human perceptions of fairness and goodness, showing that divine truth often includes correction, discipline, and the necessity of confronting hardship to foster resilience and spiritual growth. This duality highlights that divine truth is not solely about comfort but also about the harsh realities that contribute to the cosmic balance.

Virtue: Sacred and Absolute

Divine Truth is sacred and absolute, operating beyond human moral constructs of right and wrong. Unlike human morality, which is often subjective and varies across cultures, divine truth is seen as the ultimate standard that defines the moral fabric of the universe. Divine truth is unwavering and unchanging, representing a sacred order that guides the principles of life, justice, and the natural world.

This absolute nature is exemplified in spiritual laws like karma in Eastern traditions or the Ten Commandments in Judeo-Christian beliefs. These moral codes are not merely guidelines but are viewed as expressions of a divine will that dictates how life should be lived in alignment with cosmic law. The sacred nature of divine truth implies that it is not just a set of rules but a living force that governs existence with purpose and intentionality.

However, this sacred truth can often appear severe or incomprehensible to human beings. For instance, the story of Job in the Bible, where a righteous man suffers immense loss and pain, highlights the absolute and often inscrutable nature of divine justice. Job’s suffering is not a punishment but a test of faith, underscoring that divine truth operates on a plane that may appear unjust or cruel from a human viewpoint but serves a higher, sacred purpose.

Divine Truth, therefore, challenges us to look beyond our limited perceptions and embrace a broader understanding of life’s meaning. It invites us to trust in a cosmic order that transcends human judgment, balancing grace with correction, and joy with hardship. Divine Truth is the ultimate moral compass, not bound by human flaws but guiding all creation toward a purpose that only the divine can fully comprehend.

Comparing the Four Truths Through Key Historical and Contemporary Events

To better understand how Scientific, Political, Human, and Divine Truths manifest in real-world contexts, we explored four significant historical and contemporary events: the Vietnam War, the COVID-19 pandemic, the War in Ukraine, and Climate Change. Each of these events reveals different facets of truth, shaped by various forces that influence public perception and policy decisions. By focusing on the most powerful or prevalent narratives within each truth category, we can compare how these truths operate, intersect, and conflict with one another.

-

Vietnam War

- Scientific Truth: Military assessments revealed that the war was unwinnable, yet this reality was often ignored.

- Political Truth: Driven by the false “domino effect” theory, the narrative was that losing Vietnam would trigger a spread of communism across Southeast Asia, justifying immense sacrifices.

- Human Truth: The war was seen as morally wrong, sparking widespread protests and deep societal divisions.

- Divine Truth: The ideological struggle between communism and capitalism highlighted the spiritual emptiness of both materialistic systems, which were distant from God.

-

COVID-19 Pandemic

- Scientific Truth: Research on coronaviruses was financed as part of gain-of-function studies aimed at artificially creating viruses that do not exist in nature. The goal was to be faster than nature by developing a vaccine years before such viruses could naturally emerge. This approach intended to ensure that humanity would be ready with a vaccine before the virus actually exists, a controversial strategy that has raised ethical and safety concerns.

- Political Truth: The widely promoted narrative of bat-to-human transmission, taken from the storyline from the movie “Contagion” (2011), served as a convenient cover-up on both the Chinese and American sides. China, where the research took place, and the U.S., which financed parts of the research, used this story to divert attention from the gain-of-function experiments being conducted in the Wuhan lab. After the initial wave of fear, major pharmaceutical companies quickly capitalized on the research conducted in Wuhan, producing genetic vaccines without adequate prior testing. Seizing the crisis as an opportunity, these companies profited immensely, while politicians eagerly supported and promoted the vaccines, driven more by financial gain and public approval than genuine concern for health.

- Human Truth: The pandemic was marked by personal and collective experiences of fear, loss, and uncertainty. It also gave rise to suspicions and conspiracy theories, including the belief that the virus might have been invented or released on purpose to facilitate world control over populations. This narrative fed into broader fears about the loss of freedoms and the rise of authoritarianism under the guise of health measures.

- Divine Truth: Like the story of the Tower of Babel, the pandemic is a reminder that humanity should not attempt to “play God.” The message is clear: manipulating genetics and engaging in practices like gain-of-function research oversteps divine boundaries. This divine truth suggests that tampering with the natural order, especially in areas like genetics, is God’s domain, and humanity risks severe consequences when it tries to control or alter creation. But the divine truth might also frame the pandemic as part of a larger cosmic order, a challenge meant to test humanity’s resilience, compassion, or spirituality. This viewpoint often sees the event as part of a broader divine plan, where individual suffering serves a greater, often incomprehensible purpose. It suggests that what we endure may have meaning beyond what is immediately visible.

-

War in Ukraine

- Scientific Truth: Geopolitical analyses suggest that Western globalists provoked the conflict to destabilize Russia and exploit Ukraine’s resources.

- Political Truth: Dominant narratives emphasize defending sovereignty and democratic values, but these are often seen as veils for deeper strategic motives.

- Human Truth: The war’s human toll—suffering, displacement, and the threat of nuclear escalation—fuels growing animosity toward Western and Ukrainian governments, who are seen as rejecting peace.

- Divine Truth: The conflict is perceived as a necessary reckoning to expose and dismantle corrupt power structures in the West, which have been waging or financing wars for profit since the time of the Opium Wars. These wars, driven by economic greed and the exploitation of vulnerable nations, reflect a long history of lucrative conflicts. This reckoning is seen as paving the way for a better political system and, ultimately, world peace. It is a divine intervention designed to rebalance global power, purify intentions, and steer humanity toward a more just and harmonious future.

-

Climate Change

- Scientific Truth: While the consensus focuses on human-driven climate change, suppressed research suggests that natural factors like solar cycles play a significant role, revealing a biased narrative shaped by political funding.

- Political Truth: Green agendas are driven as much by economic and electoral incentives as by environmental concerns, with contradictions like the high carbon emissions from wars overshadowing the gains of green policies.

- Human Truth: Despite individual efforts to recycle and reduce emissions, people feel powerless against the broader systemic issues, recognizing that the current economic model is unsustainable.

- Divine Truth: The degradation of the Earth mirrors the spiritual degradation of humanity. As mankind abandoned God and embraced overproduction and materialism, it began destroying God’s creation, highlighting the need for a profound spiritual and moral shift to restore balance.

Conclusion

Throughout this essay, we have explored the four distinct yet interconnected domains of truth: Scientific, Political, Human, and Divine. Each truth offers a unique lens through which we understand the world, shaping our perceptions, decisions, and actions in profound ways. From the evolving nature of scientific inquiry and the manipulative tendencies of political agendas to the emotional complexities of human experiences and the transcendent guidance of Divine Truth, these categories reveal the multifaceted nature of our collective reality.

Scientific truth, despite its intent to reveal the workings of the universe, often finds itself constrained by conflicting data, evolving interpretations, and external influences. It is a process, not a final answer, and its tentative nature requires humility and openness to new insights. Political truth, on the other hand, frequently manipulates narratives to maintain power and sway public opinion, tackling problems that are beyond its capacity to solve while leaving pressing moral questions unanswered. It prioritizes control and influence over genuine ethical considerations, often sidelining the deeper issues that could lead to meaningful change.

Human truth captures the essence of our moral and emotional landscape, reflecting our capacity for empathy, compassion, and justice, yet it is also vulnerable to biases, fear, and irrationality. This truth, while deeply personal, can inspire profound acts of goodness or drive destructive mass behavior. It reminds us of our shared humanity but also exposes the fractures that divide us.

Divine Truth stands apart as the ultimate, unchanging reality that transcends human understanding. It calls us to see beyond the temporal and the material, to recognize the spiritual lessons in our experiences, and to align ourselves with a higher moral order. Divine Truth challenges us to confront the degradation of our world as a reflection of the degradation of our souls, urging us to restore balance by first healing within. Although it remains beyond full comprehension, the purpose and essence of our journey is not to fully grasp or control it, but to pursue it with an open heart and mind. It is in the striving, the attempt to understand, interpret, and approach this ultimate truth, that we find meaning.

Divine Truth is elusive, sometimes appearing just out of reach. There will be moments when we may guess it correctly, and others when we fall short. However, the act of pursuing it, of continuously seeking to align with it, draws us ever closer to God and Love. Each step in this pursuit, whether successful or not, moves us nearer to the sacred, and it is in this journey that we fulfill our spiritual calling.

Ultimately, it is the effort to understand Divine Truth, rather than its full realization, that brings us closer to the divine essence of life. By striving to understand, we grow in love, wisdom, and our connection to God.

The events we analyzed—the Vietnam War, COVID-19, the War in Ukraine, and Climate Change—highlight how each type of truth shapes our understanding and response. These events illustrate how scientific, political, and human truths often conflict, leading to incomplete or misguided actions, while the deeper, sacred truth remains overlooked.

Ultimately, the reconciliation of these truths lies in embracing the one and sacred Divine Truth. It is only by reconnecting with our spiritual foundations, confronting the moral questions we have ignored, and transcending the materialistic confines of modern life that we can hope to address the challenges of our time. Divine Truth offers a path toward purpose, balance, and peace, guiding us to honor both our humanity and the world we are entrusted to care for. Only through this alignment can we begin to heal the divisions within and around us, striving toward a future where truth is not fragmented but whole, rooted in the sacred order that guides all things.